Copyright © 2007 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

Volume 53, No 2 - Summer 2007

Editor of this issue: Violeta Kelertas

LITHUANIAN QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

|

ISSN

0024-5089

Copyright © 2007 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

Volume 53, No 2 - Summer 2007 Editor of this issue: Violeta Kelertas |

Aspects of Content and Context

Notes on My Painting

Kestutis Zapkus

I would prefer for my work to be seen first in accord with my intentions for it. Then, if the viewer wishes to give it a life outside of this base of comprehension into diverted paths of interpretation, it is the viewer’s subsequent right. I feel my specific vision is the prime factor for whatever expressive possibility my work can carry and that should be its first viewing lens. The work should fill the gaze of the viewer for an extended period of time, to go through a consideration process similar to the organization the work had undergone. The work tries to convey a thinking and a feeling process of human and world reference spread out before one’s eyes. There is no pictorial memory to take away from these articulated fields of sensations, or texts of painterly terms, presented in a visual metalanguage.

I believe I am not making objects, pictures, or societal symbols; and this is a departure from a traditional painting aspiration, where image, narrative, design, or process can be codified. I have sought to build my painting on a different premise. Using numerous episodic, associative, and formal constructs in nonlinear display, I have tried to find a visual parallel to musical composition. To reflect contemporary experience, my aesthetic prerequisite has been to indicate vast semiotic and informational fields. My organization of them has been maximalist – addressing simultaneity and complexity in a nonhierarchical, cross-referential mode. This orientation has been crucial to my work from 1959 to the present.

I see pictorialism as the bankrupt aspect of the art of painting. The overwhelming presence of mechanical pictorialization: photo, film, TV, and computer makes handmade “pictures” inconsequential. The commercialization of the picture (still or moving) for product promotion is a further assault on the credibility of anything pictorial as modernist fine art. I think it leaves my art no choice but to redefine itself according to its essential premise, the fully composed and abstractly articulated field. I am not interested in making a trivial image commodity (by hand) to share opportunities with the camera-machine and on-line advertisements. I want to compose with a rich visual language and a minimized pictorial function, to have painting operate at its basic human root, being a testimonial to the emotions, the hand, present time, and considered thought.

The following are identifications of the specific contents that generated the paintings reproduced:

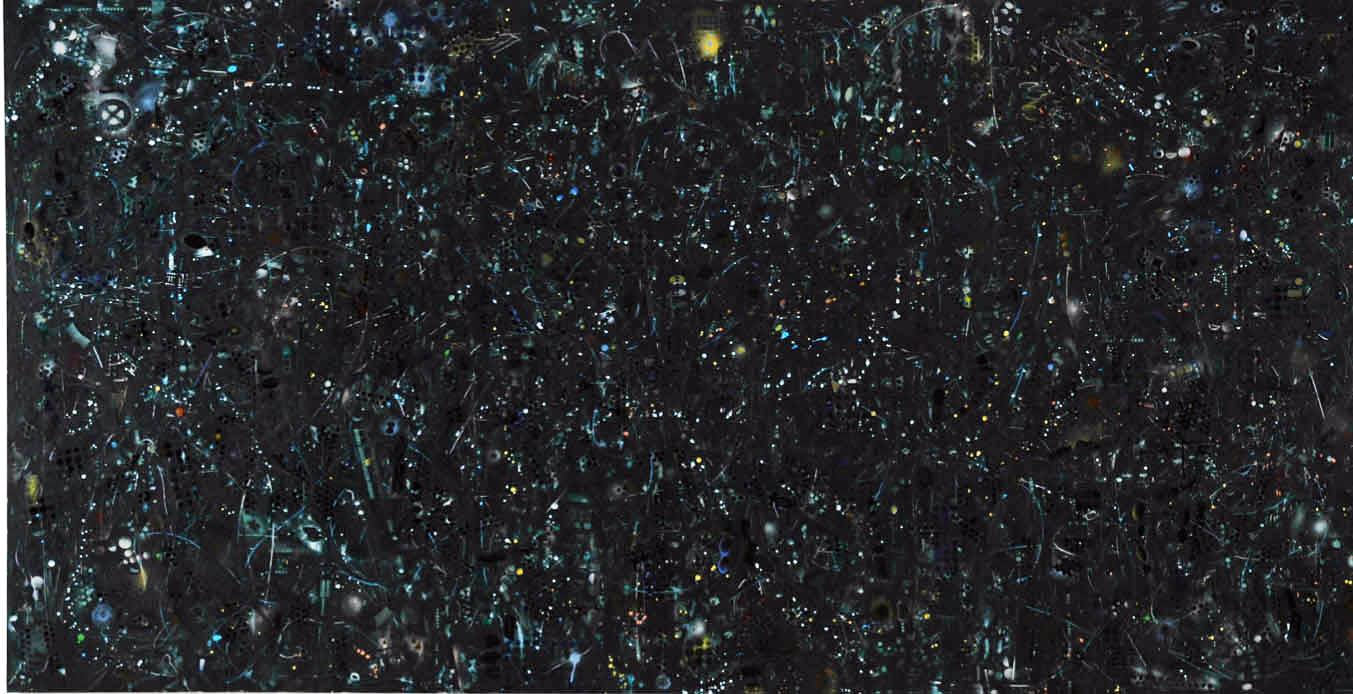

Spoof on the Bang, 2000-2001, is a large black painting about the Cosmos, but also about the unknown, the ineffable and mysterious, romantic stellar night. Without being a stargazer, my fascination with outer space multiplied with every fantastic photograph by David Malin, with the digital Mariner journey pictures and the hot flashes of images from Hubble, Schmidt, and Anglo-Australian telescopes. This now visible “unknown” contrasts the shabbiness of earthly struggles with an overwhelming blast of wonder. This painting does not paint the skies, but mocks our attempt to pin them down. It is a burlesque on the timeless superstitions and the actual minuscule knowledge of this subject. The joyride taken with gods, astrologies, and sciences reiterates the folly of counting the number of bangs to the bang. These considerations generated this painting on outer space, though the irony is on the big bang. It takes a brazen kind of calculus to fix the mapping of desire and ignorance as it accumulates to resemble evidence.

Spoof on the Bang, 78” x 144 1/4” (6.5’ x 12’ 1/4”) oil on cotton, 198.12 cm x 366.395 cm, 2000

Liberation of Past Tense, 72” x 168” (6’ x 14’) oil on cotton, 182.88 cm x 426.72 cm, 1991 to 1991

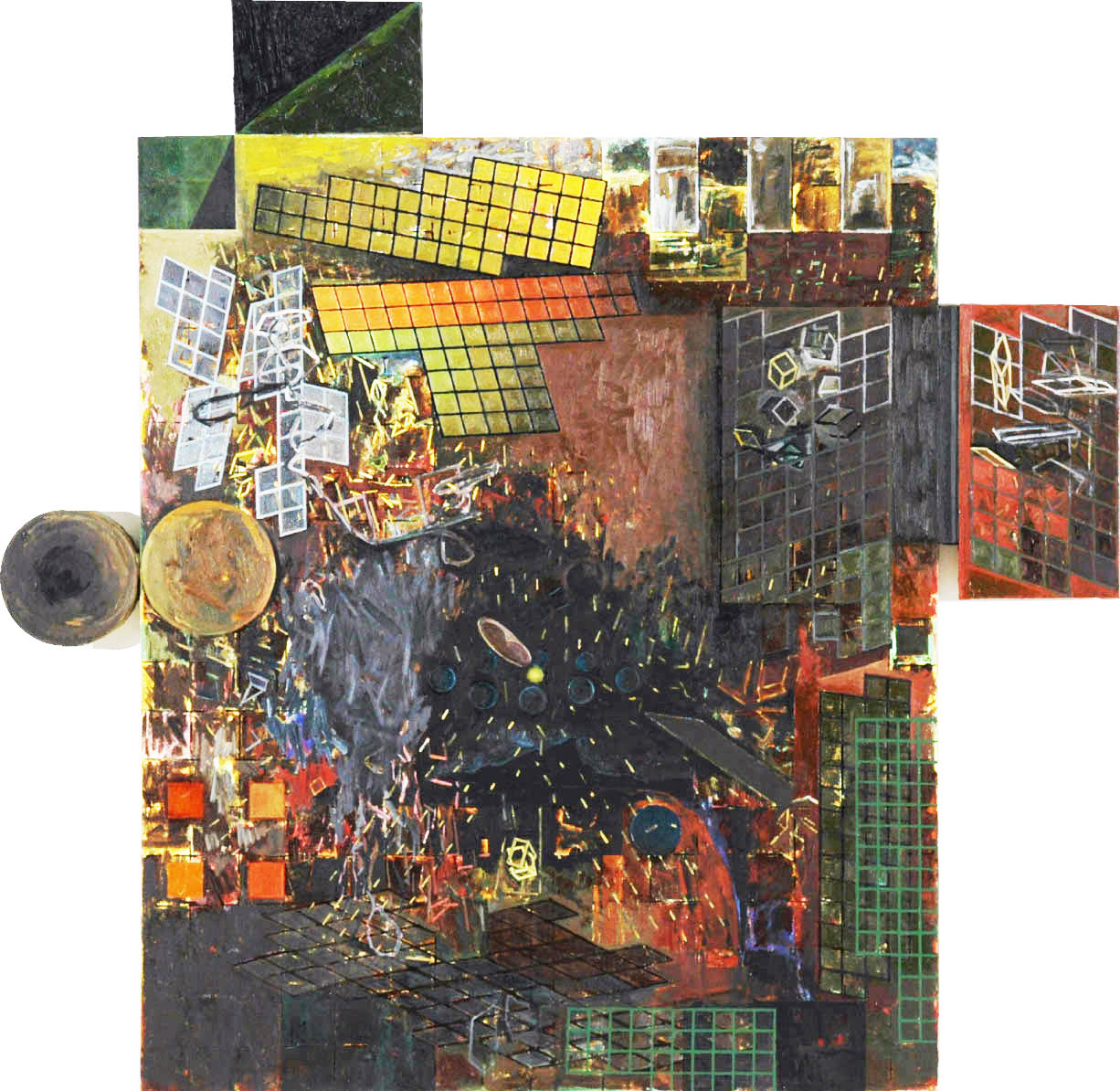

Midnight Reverie on Mont Sainte-Victoire, 1993, was an extension of this mood into a reverie on art as my religion and Cézanne’s mountain as its holy apparition. This work engages the mountain from the romance of night, situated as the central fulcrum of the work. Symbolic planets spin in the sky above; paint passages go through various modes of gestural expressiveness and recall painterly concerns of Johns and DeKooning. A panel of thickened paint (as matter) demonstrates the weakness in object-hood, regarding an immediate allusion to landscape by establishment of a horizon. Art world babble gets exercised by way of an image of my invention shown in perspectival distortion on an adjoining panel to look like a Mel Bochner calculation. An attached circular panel plays an illusionist and optical riddle, being constructed a half inch forward of the canvas plane, yet painted to appear as a recessive hole in relation to this plane.

This painting is beside itself in its delights and ruminations of the dark, on the loves of a painter. The painter’s elaborate historical, technical and emotional baggage is carried reference to be used like a blindman’s-buff on whim. Accumulative cross-referencing tentatively aspires to depth of feeling and gravity of commitment. The works of this period play conceptual games in a postmodernist field.

Midnight

Reverie on Mont Sainte-Victoire,

82.5” x 84” (6’ 10.5” x

7’) oil on cotton,

209.55 cm x 213.36 cm,

1991 to 1993

Bi-Polar Knossos, 1996-1997, is a work built of two archaeological map fragments I had kept since my student days. They were always too interesting to discard. One was of the Palace at Knossos, the other seemed related, but without any trace of identification. I had no interest in researching its identity. Instead, I was fascinated to find my thinking to be inflected by such contrary impulses: identification made one plan tangible and comprehensible, while the unnamed plan appeared very remote and unavailable. I decided to position fiction and fact as equal verities and make this a work based on false attribution and artistic liberty. I composed a long image, setting the two plans in separated extension, calling one the newer and the other more ancient, and a middle section suggesting a negotiation area to work out the differences between truth and falsehood. I entered this painting through a series of studies on paper, using photocopies and color transparencies, to examine the interconnections and rhythms of the two palace plans. The energies of the factual were arrived at in a graphic black, those of the newer or hypothetical in chemical or electric green, and the negotiation rhythms between in a sharp magenta, with traces of both sources interjected. The final large painting maintained these orientations symbolizing acquired evidence (from the studies). Many revisionist layers applied over this would be a further transubstantiation of the initial material. I had a calculated, structurally refigured Pollock idea at work here too – like a decoded identification of his drips and movements geometrized but parallel to terms of gesture and mood correlations inherent in his creative process. This work was a formulated visualization of dichotomies. Like positions in debate, intent creates intensity and credibility, which is the issue in the end, instead of factuality.

Bi-Polar Thoughts on Knossos, 84” x 168” (7’ x 14”) oil on cotton, 213.36 cm x 426.72 cm, 1996 to 1997

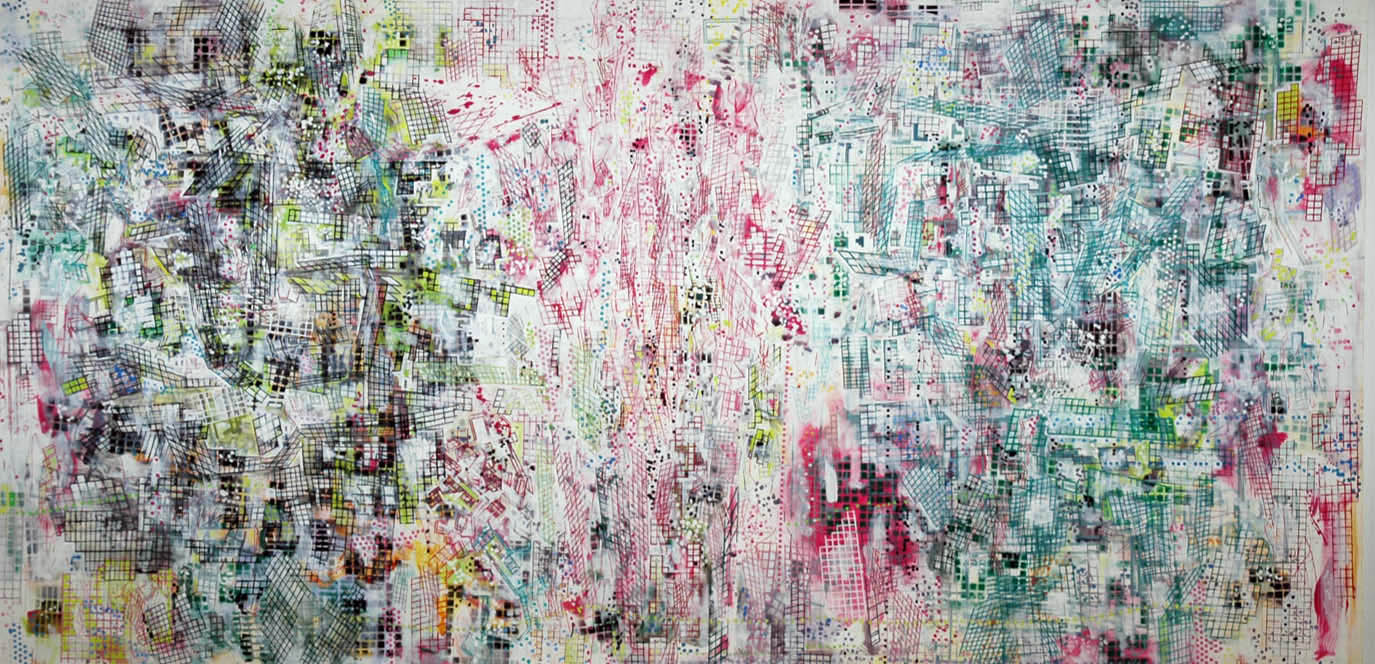

Nervous System, 1995-1997. This painting was completed, then reconsidered, sanded and completed again. It was begun in human body orientation referring to the spinal column and the endless branching nerves, with specific destinations; likewise, the idea of the cerebral cortex, connected to its billion bits of information. Later, as the process required greater control, the configurations became geometrized and strict architectural systems began to emerge. The nervous system was finally referred to the layout of a centrally controlled political or governing system. The previous version’s use of the color red for blood was now likely to convey the red of soviet totalitarianism, with its centralized power and its myriad extensions in reverberating satellite locations. The echoing church and city plan image is a generic idea to symbolize all of these systems simultaneously, while the snow-white field is stained with rosy seepage to convey growth of influence or contamination. Gray ghosts of other schemes or routes dissolving into the white suggest disappearing patterns of plans and/or abandoned functions. This work allows for assignment to theological metaphor as well. The system is nervous because it engages so many involvements and exploits its responsibilities. It suggests systems of total control become brittle from a lack of tensile strength when overextended in overreach.

Cosmic Comedy / Millennial Music, 1999-2000. The approaching Millennium created a stir from the apocalyptists, historians, prophets, numerologists and scolds. The anticipation of a new era and the passing of the twentieth century made a response inevitable, because no matter what was being done it was considered related to the event. In the spirit of social rapport, I set out to make a painting that would amuse my own prophetic inclinations as well. I included images from previous paintings, a freewheeling spatial structure with abstract illusionist and perspectival effects to further contort the ambiguities engaged. This painting is a phantasmagoria of formalist, surreal and sci-fi signifiers. Configurations are painted as matters of fact when they are phenomenalist in origin. These are contrivances and conjectures to suggest deranged technology and fantastic dynamics. The extravagant title helps to position the incongruities and temerity in the mix. No known images are depicted, yet the abstract elements are given dimensional rendering.

The millennial music aspect could be ascribed to a visual image first–the present Times Square of New York City: its lights, color, architecture, traffic, and crowds, which spin relentlessly, like a futuristic hell. The visual noise of this futurism, if first turned audial and then translated into its visual equivalent after a model of composed music, would be the perfect metamorphosed image for my use. What would a double translation do? Would a deformation or abstraction occur?

Cosmic

Comedy / Millennial Music, 78” x 120”

(6.5’ x 10’)

oil on acrylic on 198.12 cm x 304.8 cm linen, 1999

The East and West of Zero, 2001, is a smallish diptych around a large topic. The two panels are hung side by side with a three-inch space of separation. One panel is in the coloration of red, unsettled dust and the other of blue. The conceptual framework is on “ground zero,” the area of the destroyed World Trade Center Towers and was focused after a visit to and around the site. The sense of difference in the east and west of a crisis is dependent on circumstances of location. Left and right in ambulation can also figure in this equation. The left and right of politics, of religion, of psychology, of culture all refer to opposing polarities and are significant differentiations of experience. Considering the World Trade Center disaster, I wondered if having the sight of water for the destroyer or the destroyed modified their experience of it. Is the codification of a feeling dependent on the influence of surrounding factors, or is emotion pure, direct, the one issue at hand? As I think about it, I’m mystified by the range of feeling emanating from the disaster. Is it all individual or collective? As the river is to the east, the blue panel is psychologically passive and cool. As the congested city is psychologically hot and raging, this is symbolized by the red panel west. The three-inch space between the panels represents ground zero. It is all positioned in this way to act as a catalyst for reasoning.

The reasons why the insane illogic of focused harm (using oneself even as the implement) becomes possible is because of extrahuman considerations. Put religions, or otherworldly manifestations into play, and logic isn’t an issue. When people use supernatural deliberations to implement reality, fantastic imagery from fiction, movies, and religious texts becomes tangible and usable. The banality of religious and extraterrestrial concerns reveals the same retarded, backward thinking used in arguments of destructive purpose. Unfortunately we don’t consider religion, nationalism, heroics, or envy as trivial pursuits and, as a result, these societal fictions do real damage.

The diptych idea has been a continuing intermittent configuration in my painting quest. Beside the tradition of adjoined images throughout art history (from the Egyptians through twentieth-century Expressionism), there is for me another incentive, and it stems from the necessities of my form. In trying to represent the condition of totality, I see the possibility of adding on, or even another totality coexisting simultaneously. (I especially feel this working on a reduced-scale format.) So when I set up the diptych predicament, I juxtapose two notions of totality side by side, creating a self-sustaining dialectic, locking the independent actions in place.

The

East and West of Zero, 48” x 123”, oil on cotton,

121.92 cm x 312.42 cm (diptych, 2 panels 48” x 60”

with 3” separation) 2000